So far, we have used several functions in lab examples and activities, and many more in the R scripts from lecture.

Today we will be learning more about how to use functions in general through the lens of the help pages for 2 functions: mean() and var().

But what are functions, other than the names of things you type in to get your answers?

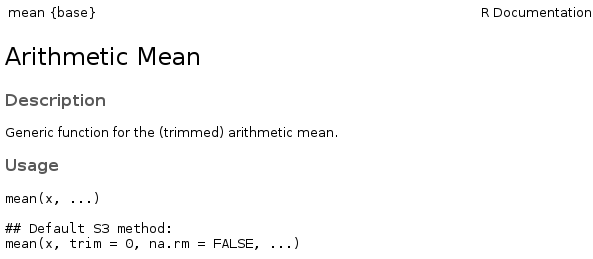

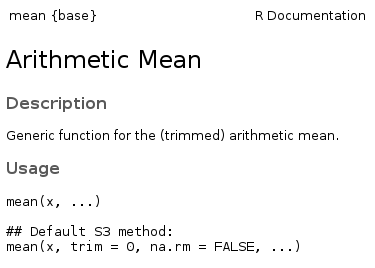

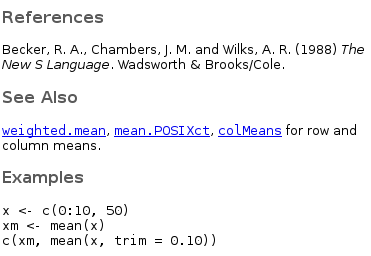

In the top left corner, you are shown the name of the help page you are on, as well as the package/namespace the function lives in.

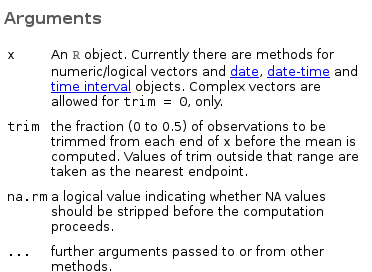

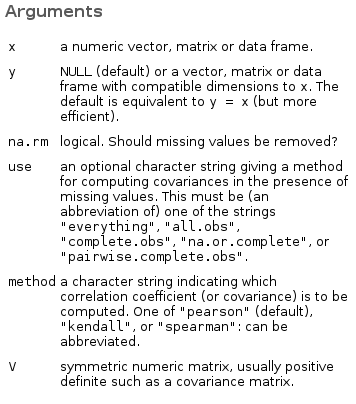

In the top left corner, you are shown the name of the help page you are on, as well as the package/namespace the function lives in. The detailed descriptions in the arguments section tell us what types of values each argument is permitted to take on.

The detailed descriptions in the arguments section tell us what types of values each argument is permitted to take on.

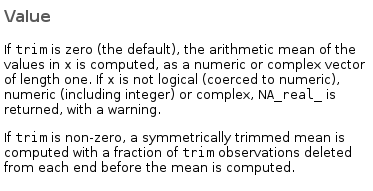

The value section tells you about what the function returns to you when it finishes its calculations.

The value section tells you about what the function returns to you when it finishes its calculations. Help pages generally end with a section showing toy examples of using the function.

Help pages generally end with a section showing toy examples of using the function.

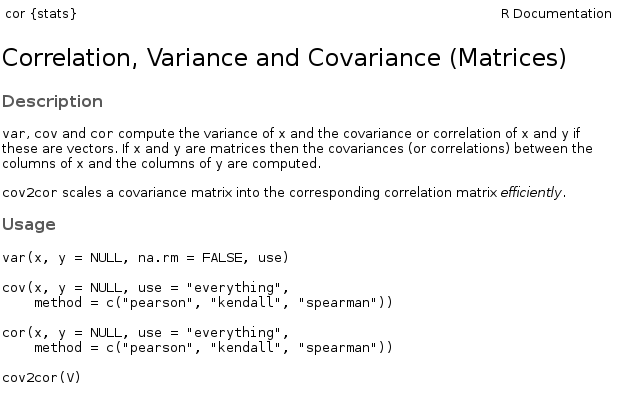

While there are 4 different functions defined here, they all have similar syntax

While there are 4 different functions defined here, they all have similar syntax